HomeShop opened its library to the public this summer. Although its collection comprises “not-yet 10,000 items,” the moment had already arrived for questions about the content, triggering a conversation that I joined the other day in HomeShop’s front space, on the issues of inclusion and exclusion.

As the library grows mostly through donations from friends and neighbors, certain patterns gradually emerge: all the books someone couldn’t take with them, some flea market novelties, something that “might come in handy.” To host anything, or hypothetically everything, would mean all the “bad” as well. Bad in the case of a library means the superfluous, the unhelpful, maybe the hateful; from another perspective, one never knows who will value what in a public library, and cutting away the inessential means cutting away part of a potential public. The central ambiguity of any archive lies on these fissures between values. This is also dependent on the reality of passing time, by which bad qualities are outlasted as a generation shifts and becomes other to itself; however, this process is most apparent in archives proper as opposed to libraries (who, in the future, will honestly cherish all of the pulp novels as books, as opposed to documents? Or do they, even at present?). One can then imagine, as did Jorge Luis Borges, a Babylonian library comprising all that was and is, in effect re-constructing the universe in type, a disorienting and endless universe in which we all dwell.

But of course other hard realities emerge to rebut this imaginary, unlimited possibility: space and order. HomeShop’s shelves are small, but not yet full. The intention of our conversation to edit the inventory—resulting, ironically, in only one or two withdrawals—therefore compromised on a discussion of what inclusion and exclusion mean. As an independent project initiated by individuals (namely, Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga and Elaine W. Ho), whose nurturing is guided by particular investments rather than indifference, the HomeShop Library recalls Walter Benjamin’s words: “But one thing should be noted: the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner. Even though public collections may be less objectionable socially and more useful academically than private collections, the objects get their due only in the latter.”(1) But with its simple principle of acquisition and circulation based on personal relations, the HomeShop collection becomes a living and metabolic portrait of a community, complicating the possessive fondness of Benjamin’s ideal bourgeois collector.

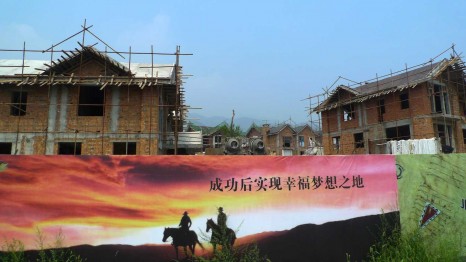

The ordering methodology can be recognized as not as rigid or as rigorous as that of Beijing’s National Library of China, though it shares the Chinese Library Classification system’s categorizations (starting, of course, with Marx & Mao, passing next through religion and philosophy, proceeding to the hard sciences at the bottom/base). But where the State institution speaks the language of publicness with its vast architectural spaces and purportedly unparalleled collection, the State’s very ordering protocols eliminate even the imaginary possibility of housing the universe on its shelves, where this could at least be a fantasy in HomeShop’s case. (A review of the oddities in the not unimpressive foreign languages section at the National Library is enough to wonder what is the basis for their acquisitions; recommendations are not invited, I was told.) The universe, after all, is composed of many, many small and particular things, not just the mapped planets and giant balls of gas. Even without space, attentiveness and affect define an alternative order of ordering. As the Indian archival project Pad.ma points out: “To not wait for the archive is often a practical response to the absence of archives or organized collections in many parts of the world. It also suggests that to wait for the state archive, or to otherwise wait to be archived, may not be a healthy option.”(2)

One pertinent irony of our contemporary media-saturated world is the State’s inability to accommodate the histories that make up the most intimate (ie. unofficial) parts of people’s lives, which actually make up the majority of all stories. But is the ambition of the (art) project to recover all lost histories, to pursue the exhaustion of this chaotic universe on its shelves? And do we hope that the State eventually takes up the pursuit of accounting for this breadth of experience? But isn’t it true that they already do to some extent, through the surveillance of all of our movements and stockpiling of all of our utterances? The gap exposed is therefore not the abyss of quantities, but the ground on which qualities are encouraged to develop. HomeShop’s library, emphasizing the knowledge and feeling that flow from individuals and can be borrowed—social exchanges, that is to say—hosts a potential to reflect the library as a universe despite or rather because of its modesty, its ethics-under-development. That said, at the end of our afternoon crusade of book-purging, we finally had to put off the decision of what to cut, until some other moment in the future.

(originally posted on the HomeShop blog, 14/09/2011. A Chinese version of this text appeared in an issue of Yishu Shijie Magazine / 中国版的这段文字会出现在“艺术世界”杂志。)—

1. Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking my library” in Illuminations

2. From Pad.ma’s “10 Theses on the Archive.” Visit Pad.ma’s alternative video archive: http://pad.ma/